There are a handful of writers I wish I’d have known. It’s a fairly short list. I’ve tried to keep it simple. Let’s start with Rimbaud. He probably would’ve been dangerous to know at any time in his life, but what the hell. It would’ve been better to go to the edge with him than hang out with some chickenshit poet who never takes chances. The most dangerous time of all to be around Rimbaud might’ve been during Scorpio when anything can happen. Try to picture Rimbaud and William S. Burroughs shooting wine bottles off each other’s heads. And, later, stoned playing russian roulette.

And Hemingway. Knowing Hemingway at any time in his life would sure as hell have been a ride. Hemingway in Paris. Hemingway in Africa. Hemingway on the Pilar. Hemingway under fire. Hemingway with the most beautiful woman in the world. Hemingway in Montana. Hemingway bellying up to any bar in the world and making it how own. And, Hemingway anywhere with a gun in his hand.

And Dashiell Hammett. The idea of hanging out with Hammett in Butte, Montana, in 1917 when the copper kings tried to hire him to kill some union guy. Hammett shadowing a fugitive for the Pinkertons down a dark Frisco street. Hammett gloriously drunk on his ass in Hollywood for years and years. Hammett in the Aleutians during World War Two and Hammett telling the House Un-American Activities Committee to fuck themselves in hell.

Last of all Bukowski. In 1970 I was just starting out as a poet. I was thirty-three years old, a college grad, stupid as hell, and had bounced out of public school teaching and then back into it. This time I’d made up my mind to write poetry. It was a do or die thing. A jump into the bonfire, a throw of the dice, an all out run to the edge. Sounds like the same old story with a slightly different twist. And, I’d been reading poetry by the carloads, the truckloads, the boatloads, the trainloads, whole libraries of poetry just to catch up. Or, at least I thought that’s what you had to do if you wanted to slap the words on the paper. I didn’t realize all it took was opening a door to the blood.

Strangely enough, it wasn’t Bukowski who pointed the way. LIFE STUDIES, Robert Lowell’s book, somehow got me digging into my own background and origins. And, I started to write about my alcoholic father and the whorehouse hotel I’d lived in with my parents, my two brothers and sister. We were holed up in two rooms, it was a cockroach infested cave. Still, we had our own toilet which was one of the perks.

For at least half of the half of the fifties I lived the life of a con artist and small time thief. Some of my best friends would graduate to burglary, arson, stickups, and murder. The only thing that saved me was an abiding idea that I was going to be a writer. Somehow, some way I was going to be a writer.

And, when I finally was able to put it all together at thirty three, I started mining the memories of what I had seen and what I had been. And, that’s when I began to read Charles Bukowski. Not in big gulps at first, because I still wanted to hold onto my own voice, my own staked out piece of authenticity and I wasn’t going to compromise that for one second. But, I still read Bukowski in quick outlaw snatches. I stuck mostly to the poetry, though I did end up reading some of the novels.

This was sometime in the late seventies when I finally knew who I was as a poet. By this time, I was writing DILLINGER and had a few chapbooks out and finally felt I had the world by the ass. Which was an illusion.

The one thing that I began to realize was that Bukowski and I were appearing regularly in some of the same little magazines. I’d known for some time that I had a writing style all my own. The short line, the quick stroke of in your face violence was my little noir invention. And, now here I was being published in the same magazines with Charles Bukowski. That, alone, gave me the added illusion that we were competing, going at it, head to head, toe to toe, mano a mano. It was an illusion that would carry me along for ten years. Maybe as many as fifteen tops.

The thing is I was competing with him but he probably had no more idea of who I was than he had of the hookers who passed him on the street. Still, it gave me something to go on. It was the gas I poured into the engine of poetry.

That whole time it seemed as though Bukowski was indestructible. I suppose it was part of his tough guy persona. Every time I think of Bukowski, I see him as a slim fortysomething show off sitting on a park bench smoking a cigarette. Just the way he holds himself there in that photo reminded me of so many guys I used to know who did the same damned thing. Or that shot of him chugging a bottle of beer as he walks along some city street. He’s oblivious to everything except the beer and maybe the way it’s washing down his throat. Or that snapshot of him bent over a book during a reading, half smirking into it, maybe in the act of heckling a heckler. Or maybe just tell the world to go get fucked.

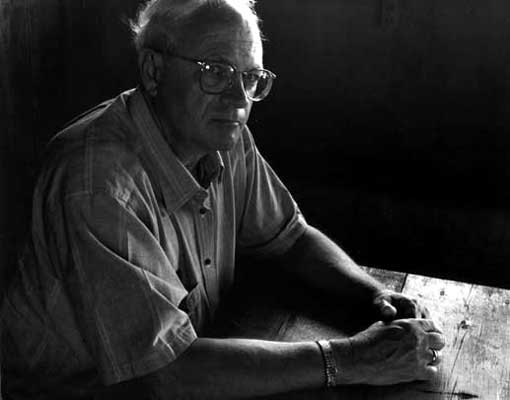

Bukowski always came across as the Bogart of poetry. The Bogie who went straight from DEAD END to THE TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE, without so much as THE MALTESE FALCON or CASABLANCE to soften the image. His face was craggier than Bogart’s. His head was oversized and almost too big for his body. The same was true of Lorca but Lorca was handsome and Bukowski was simply straight out homely. And, yet, despite his pocked looks, Bukowski head a peculiar kind of charisma. Or call it whatever you want to. Still, he gave off something like an energy charge that got your attention. It probably didn’t matter if you were watching him on video or you were there with him in person. The camera should have hated him, but instead it fell in love with his face. With that large, beaten, totalled out wreckage of a face.

And, suddenly, he was just simply a celebrity. He’d been talking about being famous for years and then it happened. And, I have a sneaking hunch it scared the shit out of him. Otherwise, why did he move out of L.A. to that little out of the way tree-lined street in San Pedro? I’ll always wonder about that.

Also, somewhere in the late eighties or early nineties the toughness went out of him. You can catch glimpses of a certain fragility in some of his later poems. The way he became obsessed with death and the way he looked in the late snapshots. Like someone or something had sucked the life right out of him.

I wasn’t surprised by the news of his death but I was shocked. Shocked in the way that I was shocked by the news of my own father’s death even though I knew he was dying of cancer. Shocked because both Bukowski and my father had been such vital and alive men.

And, for a long time, it seemed as though there was a gaping hole in that part of American poetry where Bukowski had been such a large force. And, the illusion of competition had passed away along with Bukowski. And, there were no more lies I could tell myself. Now, there was only the void to write against. Maybe that was the way it had been all along. And, I’m sure Bukowski had known that.

If anyone possessed an authentic voice in twentieth-century American poetry, it was Charles Bukowski. There was none of that mincing academic pretentiousness that you see in so many of our official poets. No attempt to be nice, obliging, or politically correct. He belonged in the company of giants, writers like Ernest Hemingway, Jack Kerouac, William Carlos Williams, Thomas McGrath, Allen Ginsberg. He was an original. Which is to say he had that certain something that makes you want to say, yeah, I’d know that voice anywhere.

Bukowski wasn’t as sophisticated as Hemingway, though neither one had a college education. Bukowski was strictly L.A. and Hemingway was the man of the world. Yet, what Bukowski lacked in sophistication he more than made up for in energy, drive, the balls-out way that he lived, and his unerring honesty about the way things are out on the street.

Even now, years after his death, his work is still as strong as ever and it’s not going to go away. Not long ago a young slam poet came up to me at a reading and said, “You know that Charles Bukowski. Shit, i’m gonna kick his ass.” I just smiled and said, “The old man’s waiting.”

This essay appeared in a slightly different form in DRINKING WITH BUKOWSKI: RECOLLECTIONS OF THE POET LAUREAT OF SKID ROW, edited by Daniel Weizmann, Thunder’s Mouth Press, New York, 2000.