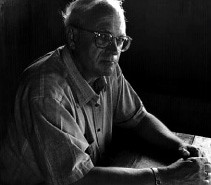

First Printing. © 2009. Published by Lummox Press POB 5301 San Pedro, CA 90733, www.lummoxpress.com Back cover photo by Pete Jonsson. Printed by CreateSpace.com | ISBN 978-1-929878-01-7. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be copied or otherwise used without the express written permission of the author, except in cases of review.

Preview sample The Riddle of the Wooden Gun – eBook (472KB PDF, 9 pages)

“Todd Moore runs with language and makes every word count.” — Elmore Leonard

“Violent, raw and riddled with humor, in time, Todd Moore’s 44 magnum opus Dillinger will take its place in the American literary canon as one of the greatest. A longtime small press hero, Moore’s gunshot staccato cannot be rivaled, there simply is no other. Literary outlaw and maverick poet, Todd Moore is a leader of the new romantic, a visionary wordslinger cut from the same bloody cloth as Cormac McCarthy.” — S.A. Griffin

“Todd Moore slaps you in the face and kicks your ass, with ink & paper.” — Joe Pachinko

Todd Moore’s poetry has appeared in more than a thousand literary journals in the last forty years. He has had more than a hundred books and chapbooks published since 1976. His work has been anthologized in THE OUTLAW BIBLE OF AMERICAN POETRY, DRINKING WITH BUKOWSKI, and LAST CALL. Metropolis, Outlaw Poetry and Free Jazz Network, Lummox, and St. Vitus are among the numerous online websites and zines which have or are currently featuring his essays and poetry. In 2004 Moore along with Tony Moffeit founded the Outlaw Poetry Movement. Presently, Moore co edits, along with his son Theron, ST. VITUS POETRY PRESS. Moore has been called a Meat Poet, a Shock Poet, a Visceral Realist, a street poet, a dirty realist, a noir poet, a pornographer of violence, and an outlaw. He has been working on the ongoing long poem DILLINGER since 1973.

Todd Moore’s poetry has appeared in more than a thousand literary journals in the last forty years. He has had more than a hundred books and chapbooks published since 1976. His work has been anthologized in THE OUTLAW BIBLE OF AMERICAN POETRY, DRINKING WITH BUKOWSKI, and LAST CALL. Metropolis, Outlaw Poetry and Free Jazz Network, Lummox, and St. Vitus are among the numerous online websites and zines which have or are currently featuring his essays and poetry. In 2004 Moore along with Tony Moffeit founded the Outlaw Poetry Movement. Presently, Moore co edits, along with his son Theron, ST. VITUS POETRY PRESS. Moore has been called a Meat Poet, a Shock Poet, a Visceral Realist, a street poet, a dirty realist, a noir poet, a pornographer of violence, and an outlaw. He has been working on the ongoing long poem DILLINGER since 1973.

And, since 1976 DILLINGER has been appearing piece meal in book and chapbook form. Hailed as both cinematic and hypnotic DILLINGER has been critically acclaimed as the best long poem of the last part of the twentieth century and the first part of the twenty first century. As an epic it rivals THE CANTOS, THE WASTE LAND, PATERSON, and THE MAXIMUS POEMS, as well as such novels as THE SOUND AND THE FURY, THE GRAPES OF WRATH, and BLOOD MERIDIAN. It has been suggested that DILLINGER is the only long poem to appear in the last sixty years which could legitimately lay claim to the title of national epic. And, Todd Moore’s essays are beginning to shape and define a whole generation of American poets. Critics now refer to Moore as a cult writer, possibly a legend. Undoubtedly, Moore is becoming one of the pre-eminent poets of the age.

And, since 1976 DILLINGER has been appearing piece meal in book and chapbook form. Hailed as both cinematic and hypnotic DILLINGER has been critically acclaimed as the best long poem of the last part of the twentieth century and the first part of the twenty first century. As an epic it rivals THE CANTOS, THE WASTE LAND, PATERSON, and THE MAXIMUS POEMS, as well as such novels as THE SOUND AND THE FURY, THE GRAPES OF WRATH, and BLOOD MERIDIAN. It has been suggested that DILLINGER is the only long poem to appear in the last sixty years which could legitimately lay claim to the title of national epic. And, Todd Moore’s essays are beginning to shape and define a whole generation of American poets. Critics now refer to Moore as a cult writer, possibly a legend. Undoubtedly, Moore is becoming one of the pre-eminent poets of the age.

America

is a nation of fierce and unforgiving images. Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry pointing a 44 magnum at a outlaw he is about to kill. John Wayne as the Ringo Kid spinning a Winchester 30-30 in STAGECOACH. Charles Bronson standing sideways while he points a pistol in a movie still for DEATH WISH. Kevin Bacon aiming his gunfinger at Sean Penn in MYSTIC RIVER. A blood smeared Warren Oates leaning into that lethal Browning fifty caliber machine gun in THE WILD BUNCH. The list is practically endless. Simply because the capacity for violence in America is also endless. Endless, hypnotic, and perversely and enormously attractive.

I’m staring at the iconic photograph of John Dillinger standing on the lawn outside his father’s house in Mooresville, Indiana. He’s holding a Thompson sub machine gun in one hand and that infamous wooden gun in the other and he’s got the biggest smile in the universe plastered across his face. I don’t know how many times I’ve studied this image but right now the more that I look at it the more I realize it isn’t just an offhand snapshot that Billie Frechette took as a whim. This image is really so much more than that. On the surface, it’s Dillinger giving the FBI the biggest finger in the world, simply because the photograph was taken shortly after he had escaped from Crown Point. Below the surface, if you know anything about Dillinger you know that the machine gun he actually carried on bank raids was streamlined. It had no wooden stock and Dillinger preferred using clips because they were lightweight. In the snapshot, this Thompson has a fifty slug drum attached beneath the barrel which would make the weapon much heavier, so you realize that this is a staged shot, meant for newspaper reporters, law officers, and the voyeur public at large. Posing for this photograph was a simple act of provocation, meant to invoke both wonder and anger from practically everyone. Or, to put it into contemporary terms, Dillinger is trying to push all the hot buttons.

However, it’s the wooden gun in his other hand that, over the years, has created the most interest. This is supposedly the piece that Dillinger used in his jail break from Crown Point. But, did he? This question, among several others, is what has made Dillinger’s wooden gun so irresistibly interesting, so undeniably desirable.

Another question, maybe more to the point of the whole Crown Point episode, is why would a man like Dillinger take such an unbelievable risk with nothing more than a wooden gun when that jail was so heavily guarded? The chances for being shot were just as good if he had been armed with a real weapon. While asking myself this question, I am for some strange reason reminded of the Russian writer Isaac Babel who rode with the Cossacks during the Russian/Polish War of 1920. Babel was a war correspondent who had somehow had insinuated himself into the thick of the action and was carrying a pistol at the time, but the pistol was not loaded. Now, why did he do that? Why would he put himself at such insane risk? Was he tempting the gods? Nobody really knows the answer to either question, and because this is the case, these actions become mysterious, enigmatic, and ultimately dangerous little psychic riddles.

In fact, that photograph of Dillinger holding the wooden gun is in itself a riddle. Superficially, it is evidence of Dillinger’s joke on J. Edgar Hoover and law enforcement in general, but in a larger sense it may also be his joke on America and in an even larger sense his own personal cosmic joke on the universe, even oblivion itself. We will never actually know. But, that won’t keep any of us from fantasizing.

What we do know is that the riddle of the wooden gun is very much a mystery that hints at darker, maybe demonic things, among them the pure sense of apocalypse in America. Naturally, we could say that the wooden gun is really nothing more than a wooden gun, maybe even a toy and leave it at that. We could also be just as superficial regarding Poe’s Raven, Hester Prynne’s scarlet letter A, Ahab’s white whale and all of its subsequent dreamings and meanings, Huck Finn’s raft, Hart Crane’s Bridge, the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg in THE GREAT GATSBY, and Faulkner’s mythic bear. But, we won’t, or rather, I won’t because these are the kinds of images, these are the haunted emblems, these are the riddles, the limitless possibilities and the dark impossibilities that both obscure and define America.

I’ve been haunted for a long time by both the story and the mythology of Dillinger’s wooden gun. Twenty years ago when I visited the Dillinger Museum in Nashville, Indiana, I saw the wooden gun displayed along with other personal effects in a glass case. Or, lets say I saw one of several extent variations of it. Since that time, I couldn’t get the image of that gun or its impact on me out of my mind. In fact, even before that I used the idea of it briefly in The Name Is Dillinger. But, I was never completely satisfied that with that version. It works fine for the section but somehow it lacks finish, fleshing out, expanded imagination, psychic daring.

At any rate, that wooden gun image boiled around inside my subconscious for at least thirty years. From time to time I might have mentioned it in a few other Dillinger sections as well, but I never really dealt with it the way that it needed to be explored. Then, one day last year suddenly and almost by surprise I began to think about the wooden gun again. Earlier in the day I’d been imagining Dillinger holding the wooden gun in that photograph and I just let that image become a kind of dream movie that looped itself around in my mind. This was going on while I was sitting in a local restaurant up near the mountains called The Flying Star. In fact, I was writing down fragmented lines on the back of a receipt from a bookstore when I glanced up and looked out on the restaurant’s patio. It was April first, ironically April Fool’s Day and the weather was deliciously warm. It was the kind of day when you knew you could literally do anything.

I was working on an ice tea and a huge chocolate chip cookie and the way the sun was slashing in at very bright yellow angles and the way the wind was blowing lightly and the way the mountains looked thrusting far up into the blue on blue sky made it all feel as though this was the first day of the earth. Then I glanced around at the people sitting out on the patio the way you usually do when you are casually eating and thinking and enjoying the feeling of just being alive and that’s when I saw Cormac McCarthy. He was sitting at a table near the wall of windows with a friend, talking, gesturing, signing a large bundle of papers one at a time. At first, I doubted that this was Cormac McCarthy but the more that I stared at this man the more I realized I was right.

I knew that McCarthy was not open to strangers and I also realized that there was something magical about this moment and approaching him for any reason would have almost certainly destroyed it. I am a great believer in signs and portents and I just wanted to enjoy what was happening because something I didn’t quite understand was taking place. Call it a kind of spontaneous duende or just simply hooking up with the power circuit of the universe; it doesn’t matter but a poem was really starting to race through me and I realized that this was not going to be a short poem. And, it wasn’t going to be something that would reasonably fit into a quick twenty pages either. This definitely was going to be longer than that. Much longer and then I was scrounging my pockets for scraps of paper to write on.

Every once in awhile I’d glance up and see McCarthy still sitting there, still as alive, still as animated as ever. I’d found a few blank pieces of paper in Chandler’s THE BIG SLEEP, a novel I’d gone back to simply because I love Chandler’s screwball narrative. I like to carry extra sheets of paper in a book I might have with me when I go out just in case I get a poem I wasn’t looking for. After nearly an hour I’d filled up all of that paper with random lines of pseudo historical and mythological references to Dillinger’s wooden gun and when I looked up again, Cormac McCarthy and his friend were gone.

The fact that he was gone made me feel as though I’d lost a secret ingredient of the poem, but by now I was so far into writing The Riddle of the Wooden Gun it really didn’t matter. I felt hugely and immensely propelled into something that for me was as important as writing The Name Is Dillinger, The Sign Of The Gun, Relentless, and The Corpse Is Dreaming. The moment I arrived home I sat down at the computer and just stayed there writing for the next two hours. The following day I did the same thing. And the next and the next and the next and the next. I worked on The Riddle of the Wooden Gun beginning with that first day in April and finally put the finishing touches on it sometime during the eighteenth, though I think I really only worked on it for fourteen days. I needed to take those few extra days to see how it would sound. It had to somehow resonate inside me. It had to light me up. I had to feel the poem fly through me like some kind of manic crow.

As far as the poem is concerned, it runs to almost five thousand lines. At least as long as Crane’s THE BRIDGE, probably longer than Lorca’s POET IN NEW YORK, nearly as long as Dorn’s GUNSLINGER. And, while Riddle is an integral part of DILLINGER overall, it could easily stand on its own as a finished piece of work. And, I believe it could easily be compared to all of these poems as well.

However, while Riddle will certainly hold its own as a long poem, what it does beyond all that is it works as one of the central keys to understanding DILLINGER. The poem, like that iconic photograph of Dillinger holding the wooden gun, and the actual wooden gun itself, is a kind of riddle much the same as the scarlet letter, the white whale, or Faulkner’s bear. None of these riddles will ever be solved to anyone’s particular satisfaction, but it isn’t really a solution that anyone is after. It’s the rich cluster of possibilities that these kinds of riddles offer. These are the riddle clusters that we all dream from. In fact, these kinds of riddles arise from a national core of dreaming, the place where we all get our faces from. And, I remain alive in the mystery of Dillinger and the riddle of the wooden gun. — Todd Moore

Much more on Todd Moore can be found via his tribute web page by clicking here…

Download

This download consists of one 572 KB PDF file containing the complete 144 pages eBook.